"I would like to join your karate practice, but I wear glasses, you see, so could I possibly skip some of the rougher stuff?"

"I am interested in aikido, but I have very sensitive elbow joints from playing high school football. Could I ask, if I come to train, that the techniques you do that are applied against the elbows not be done on me?"

"I want to try kendo, but I don't think I'd get enough of a workout in a coed class. Do you have any classes with just men in them?"

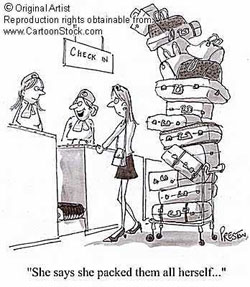

Ask any budo teacher if these requests are familiar and he will nod. Then he will probably add one or two others he has heard. Questions of this nature are typical from prospective members of the dojo. Sometimes the requests are phrased in very polite, even timid ways. Other times the prospective student, assuming he has entered a place of business and therefore may demand more or less whatever kind of service he wants, will be forceful and emphatic in outlining his particular wishes. Then, too, there are would-be students who are clever and manipulative and who will attempt to smooth-talk their way into what they want. No matter what form these requests take, however, all of them are what we might think of as "excess baggage."

When a newcomer appears at the dojo door, he really doesn't need very much, if you come to think about it, to get him inside. He should be in reasonable physical and mental health and be willing to accept what he will encounter with an open mind. In reality, he needs almost nothing else. But in his own mind the new student often arrives believing he has a great many more necessities, and he will come schlepping up with them, even before his training has begun, toting them along like the excess baggage tourists carry with them on a holiday at the beach. The student carries this excess baggage because he has the very human notion that he is special in some way, that he has liabilities or considerations that others do not have. He feels he must, in all fairness, bring these to the attention of his teacher so that the teacher will be able to deal with them appropriately and effectively in class. Although the beginner is almost surely unaware of it, even at the onset of his training, even before he may have set foot onto the dojo floor, he has reached a critical stage in his education, one that is entirely up to his teacher to handle. The teacher has two choices. He can either listen patiently and explain that he will do everything possible to take the student's needs into consideration — or he can listen patiently and explain that in no way can the dojo accommodate the excess baggage the student is carrying, and that, furthermore, believe it or not, the student will almost certainly be just fine without it.

If you encounter the sort of teacher who opts for the first approach, congratulations. You have found a cheap therapist who will reinforce all of your preconceptions about yourself. He will be sympathetic and understanding and accommodating. He will not challenge your sense of yourself, will never bring about a confrontation between you and your ego. If you run across a teacher who adopts the second kind of response, count your blessings. You may well have discovered a true sensei who can teach you things about yourself that you never knew.

The fact is, although your individual needs and shortcomings may seem very important to you, they are not really all that special. Chances are, if you can walk into a dojo under your own power, you are in good enough shape to begin training there. Of course, your asthma or your myopia or lack of flexibility may be a problem. But if you had the opportunity to ask her, you would probably discover that the woman practicing beside you is dealing with chronic arthritis. The man on the other side has a left hip that has a slight congenital deformity, and the girl behind you suffers from chronic bronchitis. And it's very likely that they all began their training by thinking their problems were as special as yours.

Another pertinent fact is that a principal attribute of the martial Ways, one of their greatest assets as paths of self-discovery and personal growth, is their breadth. Karate, judo, kendo and aikido were not meant just for the Japanese. Or just for men. Or just for finely conditioned athletes. Unlike the classical warrior arts that preceded them in old Japan and that were confined in their scope and availability to the samurai caste, the budo have a much wider aim. They were meant for everyone. And, by their nature, when they are taught, no special consideration may be given to anyone.

Got a bad right knee? then you kicks with that leg may not be as strong as mine. I've got an injury-weakened left shoulder, so my strikes on that side might not be as powerful as your. But when our sensei counts off the kicks, you must be trying your best to kick even if those kicks are not as good as mine. When punching, I have to do the same, give it my complete effort even if my best isn't going to be the same as yours. And neither you nor I can do our best when we're carrying excess baggage.

If you ever have an opportunity to attend a traditional ceremony of tea, or chado, you should take it, for many reasons. There are a number of lessons for the budoka to learn in the confines of the tea hut. Even entering the hut itself provides insight in the Way. In a properly build chashitsu, as a tea hut is called in Japanese, there is a peculiar kind of doorway, one that was designed by the great tea master Sen no Rikyu. As I have mentioned before, this door is called a nijiri guchi, which means roughly a "crawling in space." To the uninitiated, the nijiri guchi might be mistaken for a little window. It is only a few feet square. Anyone wishing to enter, to participate in the tea ceremony, must pass through this little door by lowering himself and nearly crawling throught the small passage.

The history of the nijiri guchi is informative. Sen no Rikyu's most famous pupil in the Way of tea was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the fierce warlord who ruled much of Japan during the latter half of the sixteenth century. Hideyoshi was passionate about the tea ceremony. He saw in its sober and refined elegance a goal he desperately pursued. But with Hideyoshi, it was always an inner battle between his wish for the simple beauty that he knew marked a true connoisseur, and his fevered and ambitious ego. He knew in his heart that in the quiet simplicity of the tea hut was an aesthetic to be treasured. Yet it was difficult for him to give up the magnificent clothes and the fabulously expensive swords he wore, the trappings of his satus as a shogun. He identified his position with these things, and he did not wish to be without them. (He was no different, really from the prospective students we are talking about, those who idetify themselves so closely with their own things or ideas or preconceptions or problems.) According to the traditions of the tea ceremony, Sen no Rikyu devised the nijiri guchi so that if the haughty Hideyoshi wished to enter sincerely into the spirit of tea, he would have to humble himself and crawl through the door. This architectural feature of the tea ceremony remains to this day. The tea house door is open to all. But there is only one way to enter. No exceptions can be made, regardless of one's station or circumstances in life.

The door to the dojo is different in appearance, true, but it is very similar to the tea house's nijiri guchi. There is room only for you to come in. You must leave your excess baggage outside. Trust me. Trust your teacher. Whatever you leave behind, you will not miss it at all.

©2000 Dave Lowry

RSS Feed

RSS Feed